OBJECTIVES:

The radiologist cannot determine the characteristics of a lesion if it is only shown in one projection. He/she cannot even determine if the lesion is real or illusionary. When a lesion appears only in one view on a four view routine mammogram, we have to ask ourselves several pertinent questions before we start randomly taking useless extraneous projections.

Most commonly, an apparent lesion will appear in the MLO view and not in the CC projection. This is due to the fact that more breast tissue is imaged in this projection that any other view we take. To locate the area in the CC projection should be a planned excursion not a wild ride of random projections looking for ‘something’ illusive.

The Excursion from a Lesion Seen Only in the MLO View to Placement in CC Projection:

This method of locating the missing lesion is called Triangulation. This triangulation method can be used to find the lesion in any one of three projections. Set the films up in the same manner and draw the line through the two projections the lesion is visible in.

Triangulating the MLO Lesion into the CC Projection:

The radiologist cannot determine the characteristics of a lesion if it is only shown in one projection. He/she cannot even determine if the lesion is real or illusionary. When a lesion appears only in one view on a four view routine mammogram, we have to ask ourselves several pertinent questions before we start randomly taking useless extraneous projections.

- Which projection does the lesion show in?

- Where does the lesion fall in that projection?

- Is the lesion real or made up of overlapping parenchyma?

- What can we do to find the area in another projection?

- How can we confirm that we have seen the lesion or overlapping area clearly in another projection?

Most commonly, an apparent lesion will appear in the MLO view and not in the CC projection. This is due to the fact that more breast tissue is imaged in this projection that any other view we take. To locate the area in the CC projection should be a planned excursion not a wild ride of random projections looking for ‘something’ illusive.

The Excursion from a Lesion Seen Only in the MLO View to Placement in CC Projection:

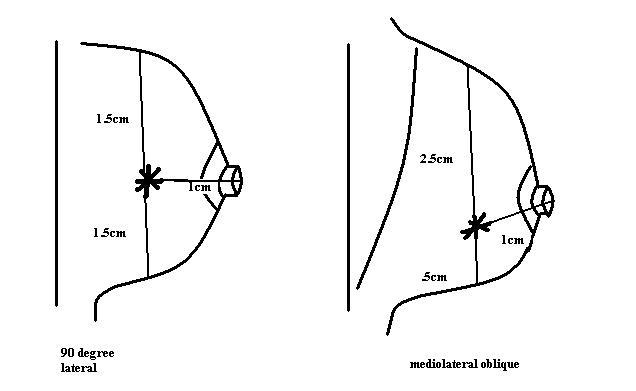

- Measure where the lesion falls in the MLO view. Take three measurements: the distance from the nipple, the distance from the superior edge and the distance from the inferior edge.

- Obtain a true lateral view of the breast, being sure to include the questionable area in the projection. Take the same three measurements: the distance from the nipple, the distance from the superior edge and the distance from the inferior edge.

- Hang the images on the viewbox with the Lateral view first, the MLO view in the center and CC view at the end. Be sure that the images are hung so the inferior/superior borders of the Lateral and MLO projections are aligned.

- Using a long ruler and a grease pencil draw a straight line from the lesion projected on the Lateral image through the same lesion on the MLO image and continue the line straight through the CC projection.

- Mark an * where the line ends at the distance the lesion measures from the nipple and that is where you will find your lesion on the CC view.

This method of locating the missing lesion is called Triangulation. This triangulation method can be used to find the lesion in any one of three projections. Set the films up in the same manner and draw the line through the two projections the lesion is visible in.

A: 90º Lateral B: MLO

Triangulating the MLO Lesion into the CC Projection:

A useful rule to remember when using triangulation to locate a lesion in the CC projection is: If the lesion rises in the lateral projection the area will show on the medial aspect of the CC, if the lesion falls in the lateral view it will show-up on the lateral aspect of the CC. “M(medial)uffins rise and L(lateral)ead Falls”

Is The Lesion Real Or Just Overlapping Tissue?

Roll/Turn View With A Real Lesion:

- Spiculated Mass

- Dense Parenchyma

A spiculated lesion overlaps a dense parenchymal shadow making the lesion indistinct and difficult to see.

- Spiculated Lesion

- Dense Parenchyma

- Superior Breast Tissue is rolled Medially

- Inferior Breast Tissue is rolled Laterally

The irregular stellate lesion is thrown clear of the dense parenchymal shadow and therefore is easily seen and a coned compression F/U view can be easily taken.

Roll/Turn View with an Illusionary or False Lesion:

- Dense irregular parenchymal shadow

- Dense irregular parenchymal shadow

Two dense irregular parenchymal densities combine to mimic a stellate lesion on the CC view. It is not clear on the MLO projection: Is it real?

- Normal Parenchymal Density

- Normal Parenchymal Density

- Superior Breast Tissue Rolled toward the Medial Border

- Inferior Breast Tissue Rolled toward the Lateral Border

Separated by the ‘roll/turn’ projection, it is obvious that the area seen in the CC projection was merely overlapping normal parenchymal tissue.

If It Is Real: Where is it in the MLO Projection?

If we see an irregular density in the CC view, prove by diagnostic F/U that it is an authentic mass, and still cannot verify where it is in the MLO view, how can we find it?

- Spiculated Lesion

- Dense Parenchymal Pattern

- Spiculated Lesion

- Dense Parenchymal Pattern

- Superior Breast Tissue Rolled toward Medial Border

- Inferior Breast Tissue Turned toward Lateral Border

In this case, the superior tissue was rolled medially and the spiculated lesion moved medially. Therefore we can conclude that the lesion we are interested in is in the superior aspect of the breast and the dense benign parenchyma was turned laterally in the inferior breast so conversely, it will be found in the inferior aspect of the breast.

- Spiculated Lesion Located in the Superior Aspect of the Breast in the MLO View

- Obviously Negative Parenchymal Tissue Located in the Inferior Aspect of the Breast in the MLO View

SUMMARY

It is our responsibility to make the lesions found in the routine mammograms apparent to the reading radiologist. The radiologist very often just tells us, “find the lesion”. If we know how to isolate, separate and identify those suspect areas we can help the radiologist, help the patient, save time, anxiety, technical resources, department finances and finally our mental health.